Asking about juries

What can we learn from a major study of the Crown Court 33 years ago?

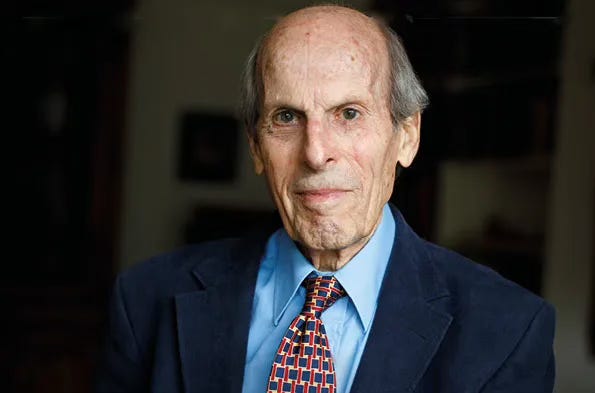

“It is a strange irony,” Professor Michael Zander KC (hon) told me yesterday, “that a study that conveys the best available empirical evidence that trial by jury is fit for purpose becomes generally available at a time when trial by jury faces its most severe threat.”

Zander, an emeritus professor of law at the London School of Economics, was referring to the 300-page Crown Court study he conducted as a member of the Royal Commission on Criminal Justice more than 30 years ago.

In those far off days, reports such as these were made available only in print (and this one cost £30). Zander has recently had the entire report scanned and, for the first time, it is available to read online.

Runciman commission

The Royal Commission was chaired by Viscount Runciman of Doxford CBE FBA. In his introduction to the report — which was uploaded to a government website some time after it was published — he made the point that juries were not included in the commission’s terms of reference because the jury system was regarded as a cornerstone of justice.

“We have received no evidence which would lead us to argue that an alternative method of arriving at a verdict in criminal trials would make the risk of a mistake significantly less,” he and his colleagues added.

Even so, the commission recommended limiting the right to jury trial in cases that can be tried either by magistrates or by a jury. Unless the prosecution and defence could agree in advance where an “either-way” case should be heard, it would be up to the magistrates to decide the mode of trial. That recommendation was never implemented.

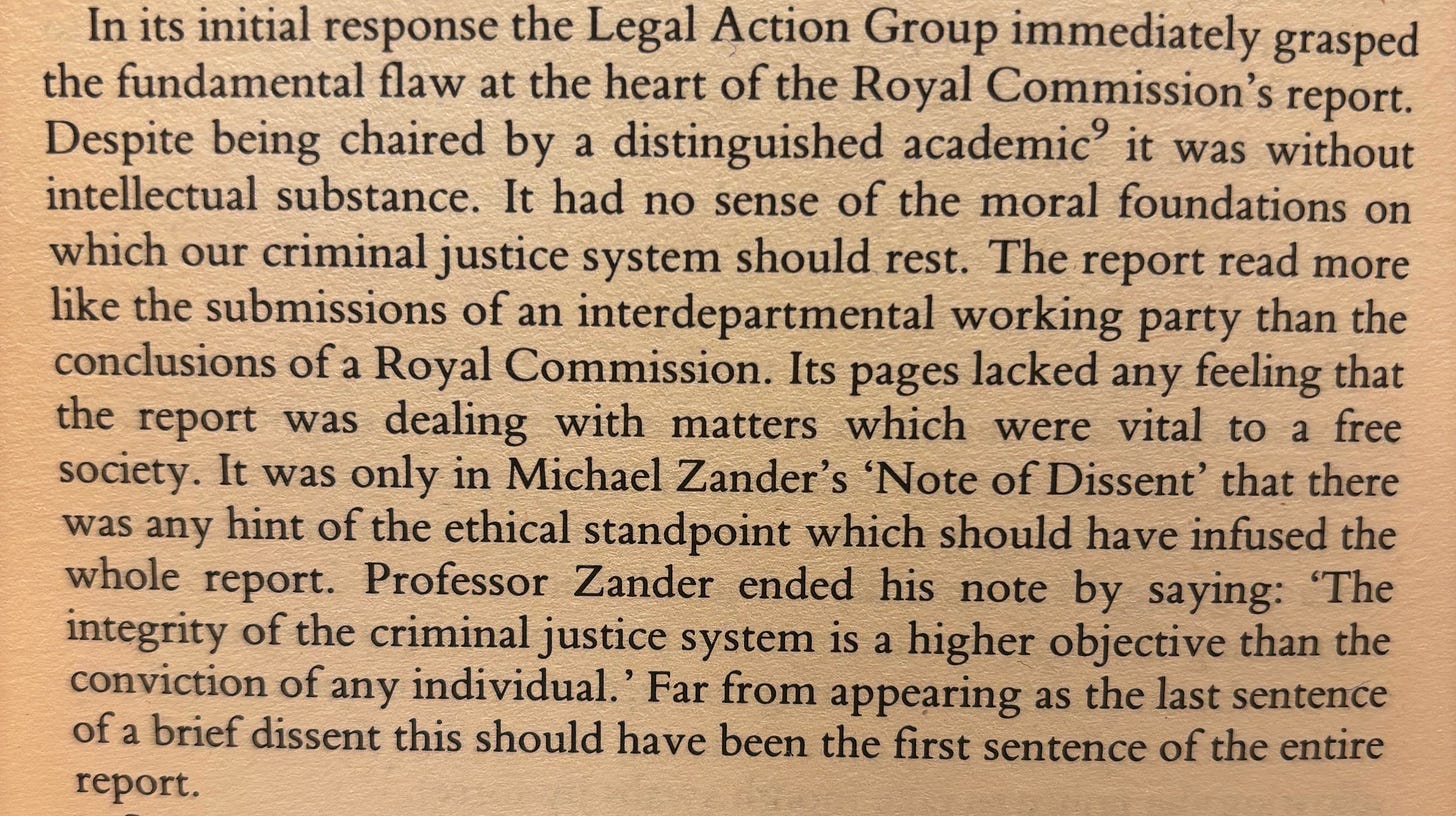

I concluded in my book The Search for Justice (1994) that the Runciman report was something of a disappointment:

Matters were not helped by Runciman’s stubborn refusal to engage with the press or public. Zander revealed that during its two years of work the commission knew “many people had built up wholly unreal expectations of its report”. He acknowledged that people were bound to be disappointed. But there was no explanation of why the commission had not tried to dampen unreal public expectations.

Runciman is credited with having recommended the creation of the Criminal Cases Review Commission. In fact, the proposal was already under consideration by the Home Office — which had consistently failed in its responsibility to recognise and remedy miscarriages of justice. The review body might have been introduced more quickly if ministers had not waited for Runciman’s recommendations.

Zander’s research

Zander’s idea was to take a snapshot of Crown Court cases by asking the different participants a series of questions. The aim was to identify problem areas and to test for weak points that the commission could address.

That’s not something which could have been done in normal times, especially if it required public funding. But what was then seen as the grandest type of public inquiry had been announced by the home secretary on 14 March 1991 — the day the Birmingham Six were cleared by the Court of Appeal after serving more than 16 years in prison.

Their wrongful convictions for 21 murders arising from the IRA’s bombing of two Birmingham pubs in 1974 were the latest in a series of miscarriages of justice. Ministers realised that nothing less than a wholesale review would have any chance of restoring public confidence in the criminal justice system. That perhaps explains why Zander’s unprecedented research was fully supported by the lord chancellor, the lord chief justice, the legal profession, prosecutors and police.

Before checking, Zander had assumed that the Contempt of Court Act 1981 ruled out any sort of jury questionnaire. As he soon discovered, jurors could be asked about pretty well anything except what was said during the course of their deliberations.

When the Royal Commission reported in the spring of 1993, legal correspondents were always going to be more interested in Runciman’s recommendations than his research reports. But Zander, who had learned a thing or two about journalism when he wrote more than 1,400 pieces for the Guardian during the 1960s, 70s and 80s, previewed his findings in the Tom Sargant memorial lecture he delivered on 8 December 1992.

That lecture was published in full by the New Law Journal three days later and is now being republished by the journal as an introduction to Zander’s Crown Court study. Part 1 of the 1992 lecture is out today and part 2 will be published by the New Law Journal next Friday.

Research findings

In summary, Zander found jurors hugely positive about the system of trial by jury. An overwhelming majority thought the barristers and judges did their jobs well. Jurors had no doubt they could follow — and remember — the evidence.

Four-fifths of judges thought the jury system was good — or very good — at getting the right result. But police and prosecutors were surprised by the outcome in about a quarter of cases heard.

There’s a great deal more about Zander’s findings in the lecture republished today. But much has changed over the past 33 years. Are Zander’s findings still relevant?

“Whatever problems the criminal justice system had in the early 1990s are probably worse today,” Zander accepts. “But why would that impact the experience of, and views about, an actual completed case?”

He had no reason to think the passage of time would have changed the way that different respondents evaluated what was done in a particular case. “The mood music about the functioning of the criminal justice system today is dark,” he accepted. “But it was dark then too.”

Comment

That’s true — but it was a different type of darkness. A third of a century ago, the system was reeling from the realisation that juries were no better than anyone else in seeing through unreliable scientists and untrustworthy police officers. We are surely more sceptical now.

At the same time, though, we are trying to cope with the consequences of years of underinvestment in an increasingly overburdened criminal justice system. It would be good to think that Zander’s historic research could help us find a way through it.

The establishment of the CCRC was indeed under consideration well before the Royal Commission reported in 1993. Sir John May’s Inquiry into the Guildford & Woolwich and Maguire convictions, in which I played a part, was already examining the Home Office’s internal procedures by the time the Runciman Commission was set up, and Sir John was appointed as a member.

In October 1991 Douglas Hurd, who had been Home Secretary at the relevant time, gave evidence to Sir John’s Inquiry. My planned line of questioning focused on the inadequacy of the internal procedures and the long delay before the convictions were referred back to the Court of Appeal. I found I was pushing at an open door.

Great article Joshua and thanks for the links out to the related material.