The Sentencing Council will never be allowed to issue guidelines about pre-sentence reports that “include provision framed by reference to different personal characteristics of an offender” if a bill published yesterday by the justice secretary becomes law.

Under the Sentencing Guidelines (Pre-sentence Reports) Bill, “personal characteristics include — but are not restricted to —

race

religion or belief

cultural background

This means, according to explanatory notes issued by the government, that courts cannot be advised by the Sentencing Council to obtain a pre-sentence report based on an offender’s membership of a particular demographic cohort. But the bill does not prevent the council from issuing guidelines advising courts to consider the offender’s personal circumstances when deciding whether to request a report.

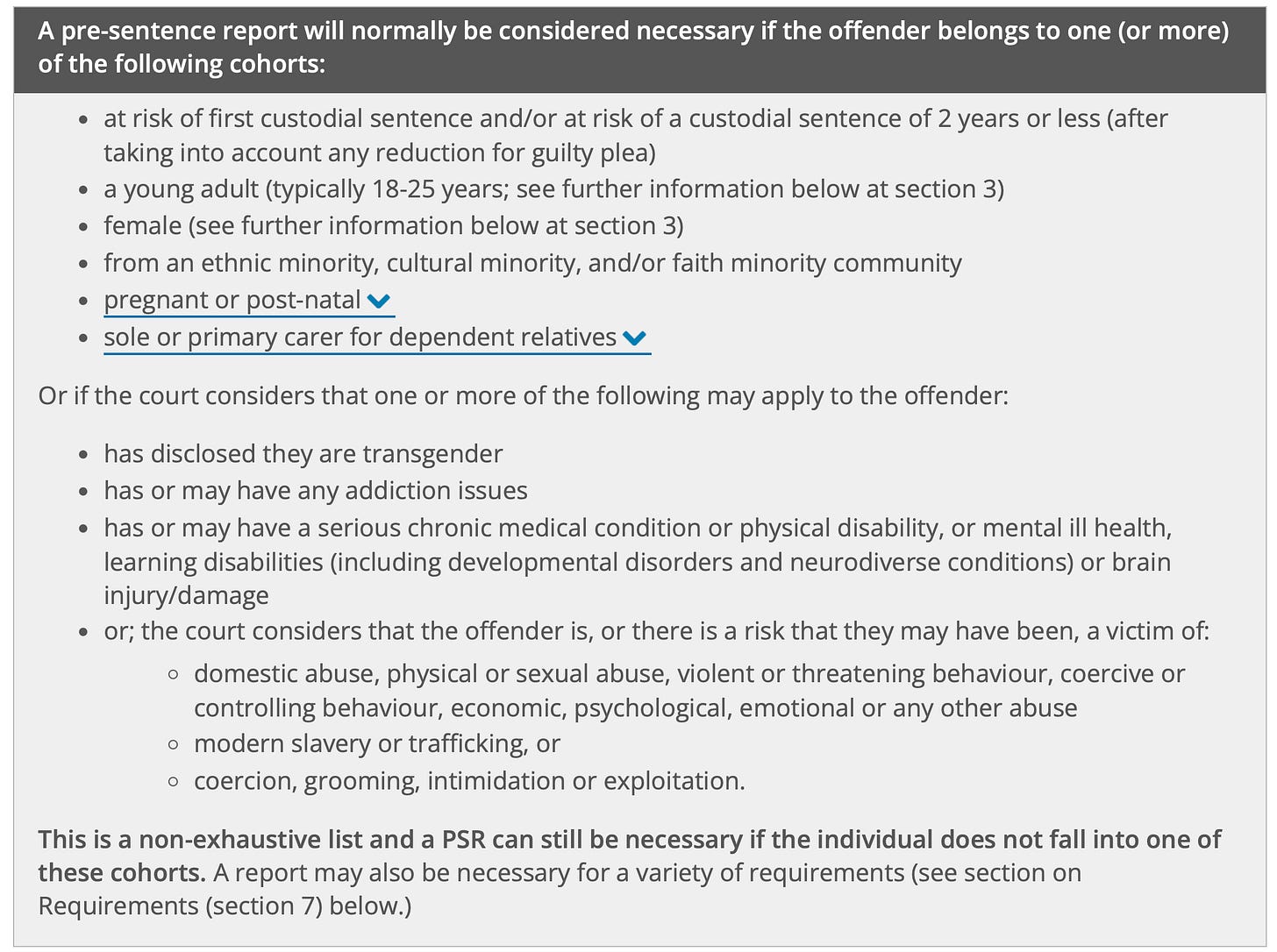

A new guideline, put on hold hours before it was due to take effect yesterday, includes this passage:

And this is the operative clause of the bill:

The legislation is intended to let sentencers consider an offender’s personal circumstances but not the offender’s personal characteristics. What’s the difference?

I suppose your circumstances mean what has happened to you and your characteristics mean who or what you are. So the “ethnic minority” cohort listed above is clearly excluded from future guidelines on pre-sentence reports while “victim of abuse” can clearly remain in.

But the Sentencing Council will have to think carefully before redrafting its guideline. What about “pregnant or post-natal” in the original list of cohorts? What about “young adult”? Circumstances or characteristics?

This is what the explanatory notes say:

Nothing in the bill prevents the council from issuing guidelines advising courts to consider the offender’s personal circumstances in deciding whether to request a pre-sentence report.

Nor does the bill affect Court of Appeal case law about when pre-sentence reports are necessary or desirable (see, for example: R v Thompson which says that where a woman who is pregnant or has recently given birth is to be sentenced, it is desirable for the court to obtain a pre-sentence report; R v Meanley where the court referred to the importance of pre-sentence reports in serious cases involving young defendants; and R v Kurmekaj where the court said that the defendant’s traumatic upbringing, vulnerability and the fact they had been a victim of modern slavery meant a pre-sentence report should have been requested).

After referring to those three cases in the Commons yesterday, the justice secretary said this:

Judges will continue to request pre-sentence reports in cases where they ordinarily would — for example, those involving pregnant women or young people.

In general, Shabana Mahmood welcomed pre-sentence reports. But, referring to reports on members of ethnic, cultural or faith minorities, she drew a direct link between a report and its consequences:

It is important to be clear about the impact that a pre-sentence report is likely to have in this instance: it is more likely to discourage a judge from sending an offender to jail. It is this that creates the perception of differential treatment before the law and risks undermining public confidence in the justice system.

Mahmood offered no evidence for her assertion that a report would make a custodial sentence less likely. In an interview I published here on Monday, the chair of the Sentencing Council took a more nuanced position.

I suggested to Sir William Davis:

One thing you do in the revised guidance is to place greater emphasis than before on the role of pre-sentence reports. Presumably, if the sentencer knows more about the defendant, the sentencer will be able to consider whether a non-custodial sentence is appropriate and what sentence to pass.

He replied:

That’s right. Self-evidently, our guidance about pre-sentence reports and the role of the probation service depends very much on the probation service being capable of producing the reports and, if the reports suggest some form of community punishment which they have to supervise, being in a position to provide the programmes and the requirements.

So, to that extent, there’s an underlying assumption. But yes, a pre-sentence report in very many cases is going to give the judge potentially the answer to what otherwise would be a very difficult problem.

That interview may have been what Robert Jenrick was referring to when the shadow justice secretary asked Mahmood this question yesterday:

Can she honestly say at the dispatch box that she has confidence in the head of the Sentencing Council, Lord Justice Davis, given that he has brought it into total disrepute — yes or no?

If she can, is she aware that he took to the airwaves yesterday, in an astonishing departure from the expected standards of judicial conduct, to advocate for abolishing short sentences, especially for hyper-prolific offenders, effectively instructing lower courts to follow suit?

It is time for him to go, and if she will not sack him for that, what will it take?

As I said on Monday, Davis recorded the interview with me on 5 March, with both of us unaware that, as we were speaking, Jenrick was politicising the issue of pre-sentence reports.

This time, Mahmood refused to rise to the bait, frequently recalling her oath to defend the independence of the judiciary and refusing to make personal attacks on members of the Sentencing Council. She responded courteously to a Conservative backbencher who was not ruled out of order by the deputy speaker despite breaching a long-established rule of parliamentary procedure:

The exchanges on 12 February and Baroness Carr’s response are reported here. But it’s clear that the lady chief justice did not regard this as a question of policy for parliament. And whether the justice secretary can justify saying that her new bill is also a matter of policy is something I shall discuss in my much-trailed column on Friday.

Oh dear….i can see a few magistrates scratching their heads (again….think increase then decrease then increase in sentencing powers)…imagine you are struggling to maintain your minimum sittings quota(13 full days a year),doing the never ending online training coupled with the ad hoc changes to technology (multi factor authentication…but you still need to change your password every 2 weeks) and now ,what appeared a relatively straightforward element of the job:

1. If a community order is required a PSR is obligatory unless there is a recent one already available.

2. If custody is inevitable then there is no need for a PSR

3. People who may go to prison for the first time or have others dependent on them (similar to extraordinary circumstances in ‘toting’ cases) …should have a PSR .(common sense really)

4. As there is a statutory route to avoid a PSR , when asked for advice by a very confused bench the Legal Advisor will rightly say..”it’s a matter for you your worships…”

All this in the face of ever dwindling numbers of criminal barristers (an entire day last week in an NGAP court with Litigants in Person…mostly no insurance therefore no duty solicitor (although she did help when she could) and LA spent the day explaining “strict liability “ …so a waste of court time ….if you now make this duty so onerous/ridiculous/technical many of the criticisms aimed at the magistracy by secret barrister etc will become true. I’m not sure if it was in the Sir William interview ,but he talked about needing another 4-6000 magistrates…..if that is true then this unseemly squabble is pretty much the worst advertising campaign ever!

Thank you Joshua, your ongoing coverage of this saga has been excellent.