Justice delayed

The jury is still out

Legislation to limit the availability of jury trial in England and Wales will not be introduced before “the spring”, David Lammy told MPs yesterday. The justice secretary said he hoped his planned courts bill would complete its parliamentary passage by the end of 2026.

Asked by the committee chair Andy Slaughter whether ministers would be issuing a formal response to the recommendations made by Sir Brian Leveson in a report published seven months ago, Lammy said that a response would also be published in the spring.

“The spring is a moveable season,” Slaughter observed — perhaps recalling that, in Whitehall, spring may continue until August.

“Spring” is also when Lammy expects to receive the second part of Leveson’s report, in which the former judge will be recommending ways of making the courts more efficient. But that’s not expected to require legislation.

Would Lammy be limiting jury trial if the backlog of cases of cases awaiting trial in the crown court was not as high as 78,000, and rising?

“Modernisation is required anyway,” the justice secretary replied. The criminal courts had not been reformed since the Courts Act 1971 had replaced assizes and quarter sessions with a permanent crown court. And cases had become much more complicated in the meantime.

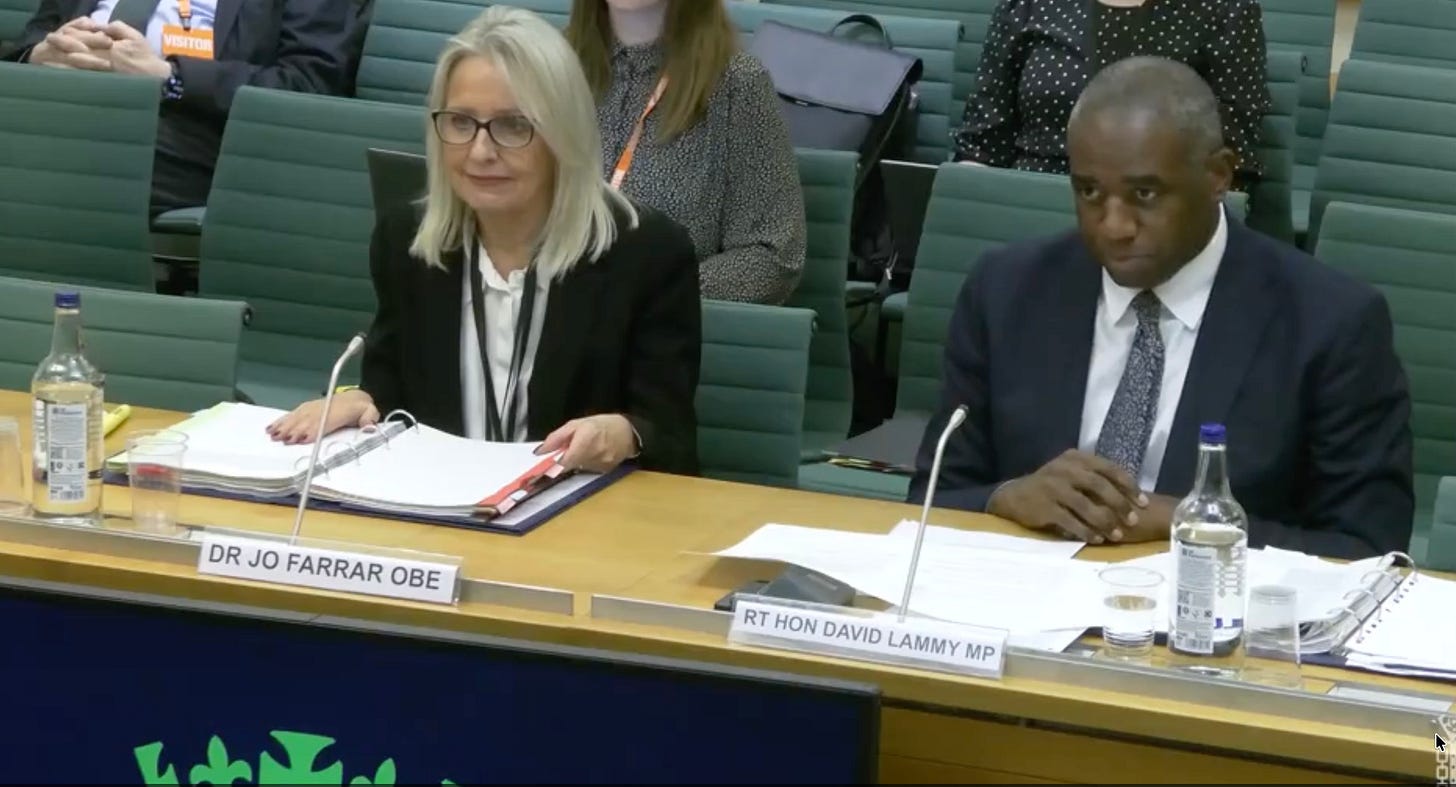

Lammy was accompanied by his most senior official, the Ministry of Justice permanent secretary Dr Jo Farrar CB OBE. Unsurprisingly, she was not asked anything by the committee. Perhaps more surprisingly, Lammy did not invite her to deal with questions to which he had no immediate answers and she chose not to help him out, remaining totally silent throughout the two-hour session.

Details

In a letter sent to the committee on Monday, Lammy responded to questions he had been asked by Slaughter shortly after he had announced his plans:

Asked what proportion of the approximately 3 per cent of criminal trial cases that proceed to a jury trial in the crown court would still get a jury trial post-reform, he replied “over half”. This figure applies only to cases that proceed to trial because the defendant pleads not guilty.

Asked how judges would decide whether an either-way case would meet the threshold for trial in the proposed crown court bench division — a likely sentence of three years or less — he said the likely sentence would be decided in line with the sentencing gidelines. Judges would consider likely culpability and harm as well as the usual aggravating and mitigating factors. Both the prosecution and the defence would have the opportunity to make representations on likely sentence before a decision was reached on mode of trial. Any triable either-way offence deemed likely to receive a sentence of over three years would be allocated to a jury trial, as would all indictable-only offences.

Verdict

Lammy’s comments in parliament confirmed the conclusion I drew in yesterday’s piece that ministers are still working on the details of their proposals. “Where do we find exactly what the government is proposing to do”, asked Slaughter, echoing my point that there should be be a white paper setting out the government’s plans.

In response, Lammy seemed to hint at the possibility of a draft bill. That was a suggestion made to me by the courts minister Sarah Sackman — and then immediately played down by her — in an interview I published on 5 December. But perhaps I am reading too much into their comments.

The justice committee’s biggest concern at the moment appears to be that the government has not produced the evidence needed to support its proposals. Lammy’s constant refrain is that delays are bad for victims; reducing jury trial will speed up justice; and therefore the reforms are good for victims. Leveson’s argument is that modelling is difficult because there are so many variables. Lammy says it all depends on how many sitting days he can agree with the lady chief justice. But unless the justice secretary can come up with some reliable figures he will not persuade even Labour-supporting lawyers that he needs to implement such radical reforms.

Rivlin

During questions in the chamber yesterday, Lammy was asked by the Conservative backbencher Sir David Davis KCB about a powerful critique of Leveson’s proposals by Geoffrey Rivlin KC, formerly the senior judge at Southwark Crown Court.

Rivlin offers an insight into the views of the judiciary, who have not spoken publicly on what they see as an intensely political issue. He writes:

Quite apart from any principled objections to judge-alone trials, which should not be underestimated, my concerns are that these proposals present a range of intensely practical problems — problems, without any sign of workable solutions, which would be bound to do more harm than good.

Lammy seemed unaware of Rivlin’s concerns but advised Davis not to reject Leveson “out of hand in that way”.

PACCAR

The Ministry of Justice has said it will introduce legislation “when parliamentary time allows” to reverse the effect of a controversial judgment delivered by the Supreme Court in a case called PACCAR.

The court held in 2023 that litigation funding agreements which allowed funders to keep a percentage of any damages recovered amounted to “damages-based agreements”.

As a result, many agreements became unenforceable and it has been harder for claimants to obtain litigation funding. The ruling had also threatened the UK’s status as global leader in dispute resolution, in the government’s view.

Ministers said their proposals would again enable collective actions to be brought against powerful defendants, as had happened the Post Office case.

Update: parliament has now been informed.

"The ruling had also threatened the UK’s status as global leader in dispute resolution, in the government’s view." The UK's status as global leader in anything apart from idiocy has been destroyed by the wrecking ball called Labour. It's quite an achievement to raise inflation, immigration, unemployment and the taxes that pay for immigrants whilst simultaneously lowering education standards, increasing the backlog of NHS hopeful waiting for their turn in the ever increasing length of a queue which only the indigenous population is subject too, AND at the very same time, totally eroding any trust in government, causing a mass exodus of the affluent, AND ensuring that the value of property, the stalwart of the economy,is diminished daily by both actual budgets and manipulative leaks as to inane, ill thought out policies.

So whatever lammy does or does not achieve is bound to simply compound the rot.

There is a lot to unpack with these proposals. I am one of those people who don't have fully tinted glasses in respect of juries. There are a lot of odd decisions reached, but on balance they are probably a good thing. However, I do think it is legitimate to consider whether the balance is correct in terms of the number and range of cases that go to jury trial.

The removal of magistrates from the Crown Court bench is presumably partly practical in that (a) the number of magistrates is dropping each year, so are they confident they could get enough, and (b) many magistrates cannot sit for a block of time (say a week) to do a trial, so you would end up with an unrepresentative bench (assuming 'representative' means anything).

We are seeing this "likely sentence" provision in a few pieces of legislation now. It is an odd way of expressing things and requires the relevant court to look at the sentencing guidelines and many of the facts, some of which will be untested. Many allocation hearings take place at the first hearing when plea before disclosure, etc. so a lot of the facts, aggravating and mitigating features are not known at that point. It would certainly have some startling results. The vast majority of s.20 will see a sentence under 3 years. Only category 1 and 2A fraud would see a sentence potentially in excess of 3 years. Most sexual activity with a child would attract a sentence of three years or less...

It will also be interesting to know when allocation is decided. Will it be the magistrates deciding not only whether it's suitable for summary trial (18 months under the proposed rule) or not, or will they also be deciding whether it's Crown Court Division or Trial on Indictment, which would involve them deciding whether a sentence is likely to be in excess of three years, something they do not currently need to decide?