The much-admired legal commentator David Allen Green made an interesting observation last week about the Supreme Court’s ruling on the Tate Modern and its viewing gallery. By a majority of three to two, the justices agreed with neighbouring residents that the gallery was committing the common-law civil wrong of private nuisance. But although both Lord Leggatt for the majority and Lord Sales for the minority cited a dazzling array of cases going back centuries — and although they both referred to a case on this topic that many lawyers will remember from their student days — there was no mention of the judge who gave the first judgment in that case.

Still less did any members of the court quote the most memorable lines from that judge’s ruling in 1977:

In summertime village cricket is the delight of everyone. Nearly every village has its own cricket field where the young men play and the old men watch. In the village of Lintz in County Durham they have their own ground, where they have played these last seventy years. They tend it well. The wicket area is well rolled and mown. The outfield is kept short. It has a good club-house for the players and seats for the onlookers. The village team play there on Saturdays and Sundays. They belong to a league, competing with the neighbouring villages. On other evenings after work they practise while the light lasts. Yet now after these 70 years a judge of the High Court has ordered that they must not play there anymore. He has issued an injunction to stop them. He has done it at the instance of a newcomer who is no lover of cricket.

That could only have been the work of Lord Denning, who was master of the rolls from 1962 to 1982 — and who before that had sat for 18 years in the High Court, the Court of Appeal and the House of Lords.

Why not mention him by name? The main reason must be that, not for the first time, Denning was in the minority on the main issue. Lords Justices Geoffrey Lane and Cumming-Bruce, sitting with him, held that the cricket club was committing a nuisance by failing to stop sixes hitting a neighbouring house and garden. There was no obligation on the claimants to protect themselves in their own home from the activities of the defendants. The master of the rolls, as one might infer from his introduction to the case, would have found for the cricketers.

However, Denning did persuade one of the other judges that it would be in the public interest to lift an injunction previously granted to the homeowners. They were instead awarded damages to compensate them for broken roof tiles and cricket balls landing in the shrubbery, or worse.

Was there another reason for not mentioning Denning? Would any reference to him have detracted from the authority of the Supreme Court’s ruling? Though Denning’s judgments can still be read with pleasure, his judgement was utterly discredited towards the end of his legal career.

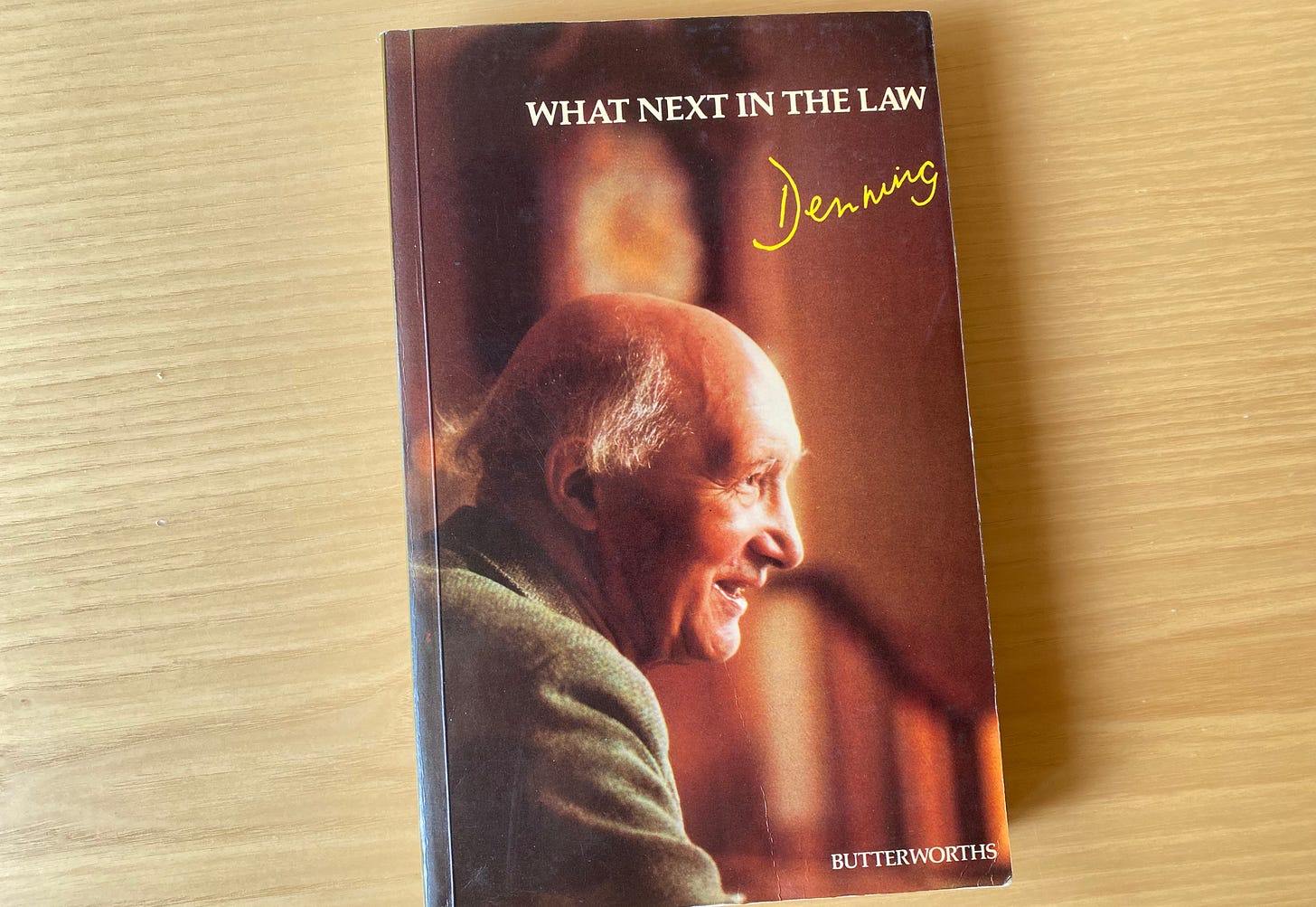

This book was his downfall:

Returning to the fray in a later column, Green quotes from one of Denning’s best-known misjudgements — the “appalling vista” case — while adding that he had no idea what Denning was like as a person.

Perhaps I can help: I met Denning a few times, and in checking some references for this piece I found a unique recording of the last words he spoke from the bench as a serving judge. It’s a fascinating listen.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to A Lawyer Writes to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.