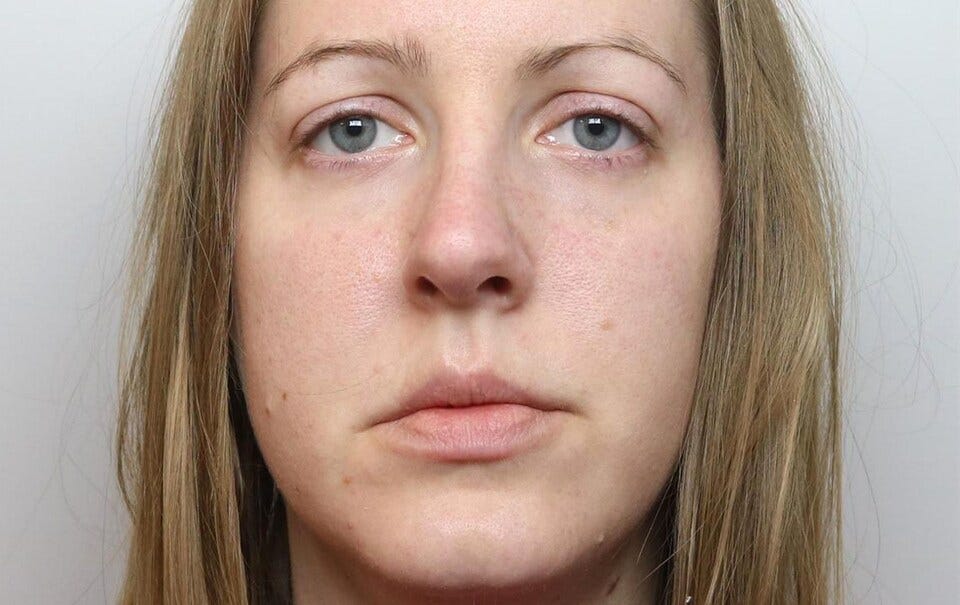

Why have the Telegraph and the Daily Mail led their coverage of the Lucy Letby case this morning with her expected non-appearance in court for sentencing?

The Mail quotes a father whose twin boys Letby tried to murder:

What gives her the right to refuse to come up from the cells or to tell the judge that she doesn’t intend to listen to his sentence? The l…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to A Lawyer Writes to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.