The county court is the Cinderella service of the justice system in England and Wales, the Commons justice committee says in a report published today.

MPs describe the court that decides money actions, tenancy disputes and personal injury claims worth less than £100,000 — along with more than 351 other types of case — as “beset by delays”. This is the result of a “failed attempt at digital reform; recruitment and retention issues; and a complex and dysfunctional patchwork of outdated paper-based and digital systems,” the report adds. “It is not tenable to continue without fundamental reform.”

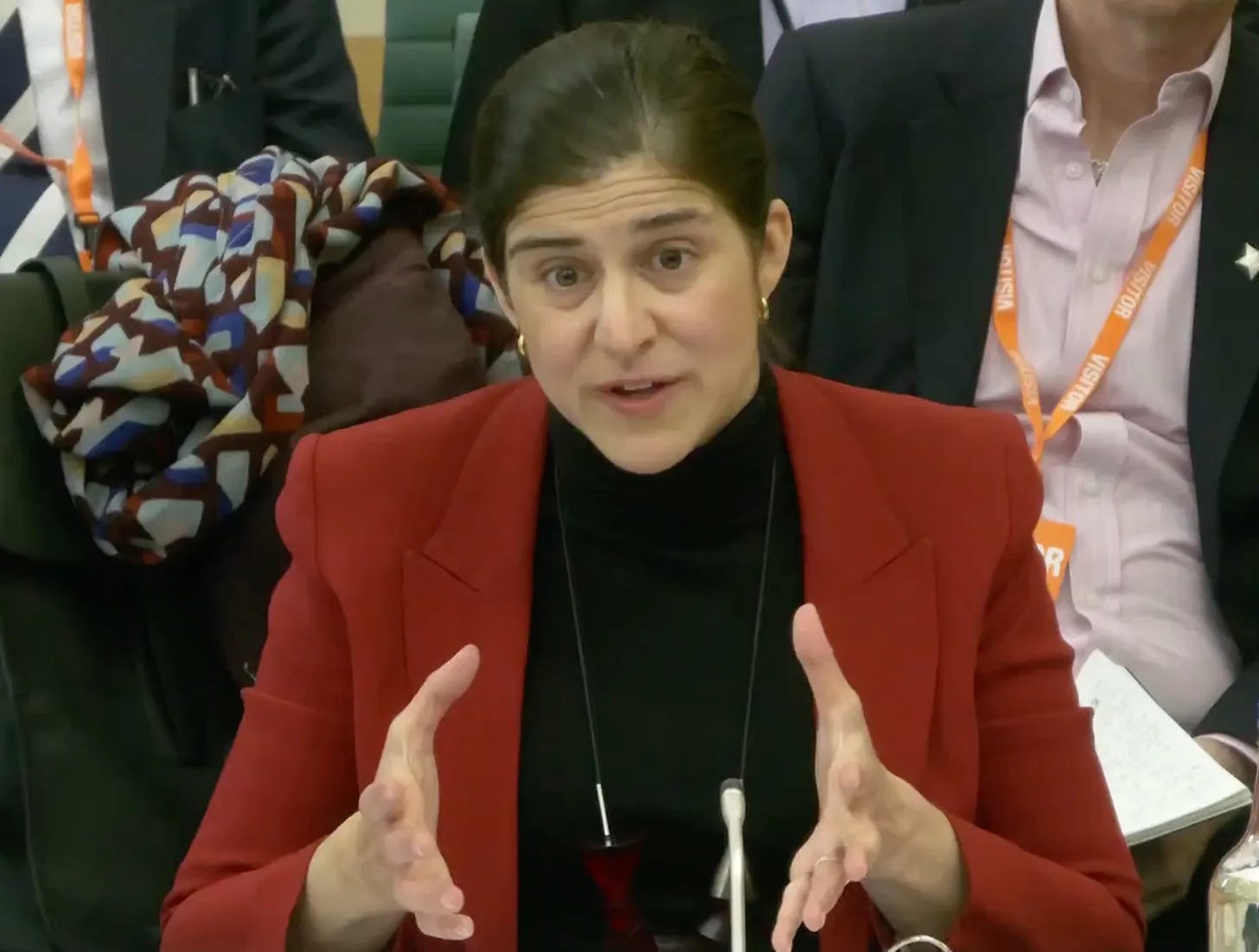

The committee’s conclusions come as no surprise. As I reported at the time, the courts minister Sarah Sackman admitted when she gave evidence to the committee on 8 April that there was “room for improvement”. Readers may remember this as the occasion when Sackman and her officials outnumbered the MPs who turned up to question them.

“Our report finds that the county court is a dysfunctional operation that has failed to adequately deliver civil justice across England and Wales,” the MPs say. “It is the ‘Cinderella service’ of the justice system. This has never been more evident than when compared to the reviews currently underway into both sentencing and the criminal courts and the fundamental absence of any equivalent review of the civil justice system.”

They continue:

We found that the situation in the county court is dire and requires urgent attention…

Therefore, we recommend that an urgent and comprehensive root-and-branch review of the county court is undertaken to establish a sustainable plan for reducing the systemic delays and inefficiencies entrenched across its operations.

Our report raises serious concerns over the current level of delays across the county court… The latest annual statistics show that currently it takes over 50 weeks, on average, for a small claims track case to be heard.

Reform

As the name suggests, county courts were originally run locally. Each court used to print its own application forms, known as praecipes. A centralised system was established in 2013 when parliament created a single national county court.

The committee said:

Despite its intended aim of simplifying the operation of the county court, the centralisation of essential court operations has had a devastating impact on the delivery of justice, entrenching the postcode lottery and results in debilitating delays for all parties.

The current methods of contacting a county court do not work. Users cannot find the necessary contact information, and centralised inboxes and phone numbers appear unmonitored as they fail to provide the required response rate.

A retired solicitor of 40 years’ standing who provides legal services to consumers on a charitable basis gave the committee some examples:

The county court at Sheffield answers its calls promptly. The county court at Barnet does not answer its calls at all. The county court at Romford no longer has a telephone number. One must instead call a central inquiry line whose call handlers are unable to answer queries but can pass messages to the Romford court, which might or might not deal with them.

The same lawyer accused half-a-dozen bulk litigation firms representing car parking concessions of systematically abusing the county court process, causing widespread injustice and misery in addition to clogging up the system to the detriment of other users.

Law Society

Solicitors’ leaders called for greater investment. Richard Atkinson, president of the Law Society, said:

Recent reforms have not worked. Over 50% of solicitors we surveyed do not believe that the new online portals are effective in delivering justice, with the main impact being delays to the wider justice system.

Court buildings need repairs, systems and technology must be fit for purpose and civil legal aid needs urgent investment across all areas. Robust data collection should track and drive systemic improvements.

If the government properly funded our courts and those who work in them, thousands of people would be freed from the legal limbo caused by long waits.

Master of the rolls

Giving oral evidence to a different parliamentary committee last month, the head of civil justice Sir Geoffrey Vos explained that attempts to digitise county court had proved “massively difficult” because nobody involved had “started from an understanding of all the multifarious, different, disparate kinds of cases we do”.

The master of the rolls told the Lords constitution committee:

In one county court, in Luton, for example, wherein is the home of easyJet, they have lots of airline delay claims. It’s not surprising, but they are of a completely different character from the county court in Birkenhead, where they have what we call stage-three personal injury claims in hundreds and maybe even thousands.

So if you’re trying to make a system in which one-size-fits-all, you can’t, and so you really need to tailor the process for civil justice in a very different way from the way we did it for family justice and the tribunals of various kinds where the cases tend to be homogenous — they tend to all be roughly the same with the same kinds of parties.

But Vos was optimistic:

The solution to getting the paper out of the county court is now on track, I believe, finally. We’ve created these two digital systems, online civil money claims, which is for debt claims effectively, and another very good system: they’re both very good systems for damages claims.

What we now need to do is to expand them because, as of today, only about 11% of cases starting in the county court go through those systems. We need to expand them so that they can accept many more of the various different kinds of county court cases.

Again, it’s doable. The reason why it’s not been done to date in many cases is not indolence, not unwillingness, not even a lack of collaboration. But what it is is that all these different types of cases have different archaic rules that apply to them, they have different fees that apply to them, and the digital system was built for simple debt claims and simple damages claims and needs to be tweaked, adjusted, or the rules need to be tweaked and adjusted, or the fees need to be tweaked and adjusted, and then we can bring a whole raft of other types of claims on board.

Vos is responsible for 140 county court centres in England and Wales. Many of them were running efficiently, he said, but delays were caused by problems at the central civil national business centre in Northampton — “where they had five floors of paper and it took weeks, months sometimes, to get those cases out to the county court”.

A government response to the committee’s report is expected in the autumn.

There are 38 types of claim that are “commonly” brought in the county court.

That ‘attempts to digitise county court had proved “massively difficult” because nobody involved had “started from an understanding of all the multifarious, different, disparate kinds of cases we do”‘ comes as no surprise. I recall many years ago being present at a conversation with someone who was engaged in a MoJ project to look at appointing District Judges from outside the pool of qualified solicitors and barristers.

He explained how they were working on several “models” including the possible appointment of lay people. “How many visits to a county court have you made to see what District judges do?” he was asked. “Oh none, he replied”.