Emergency state

And what did the judges do to stop it? Should they have done more?

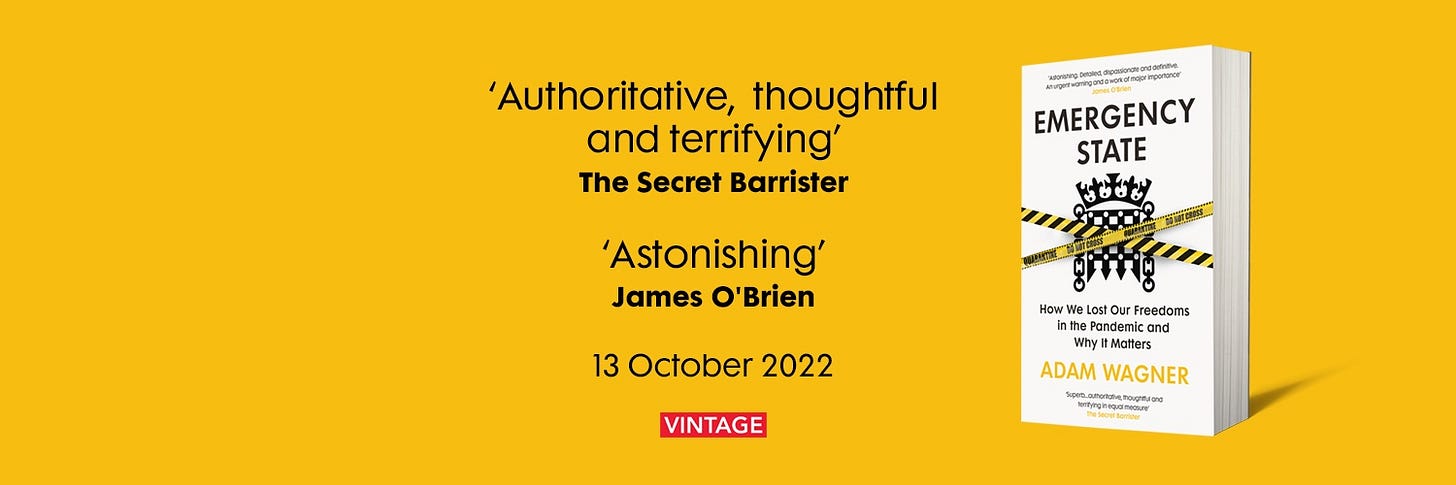

Adam Wagner’s book Emergency State is not published until next week but he’ll be talking about the issues it raises on Start the Week this morning. So I don’t think anyone will mind if I write about it today.

Wagner, a barrister at Doughty Street Chambers, started to keep a tally of the emergency coronavirus regulations when the first of them was publish…