Who’s to blame?

Why did China spy trial collapse?

One of the strangest aspects of the recent China spy trial “disappointment” is that prosecutors thought a judgment from the Court of Appeal in a similar case last year had made it harder for them to secure a conviction.

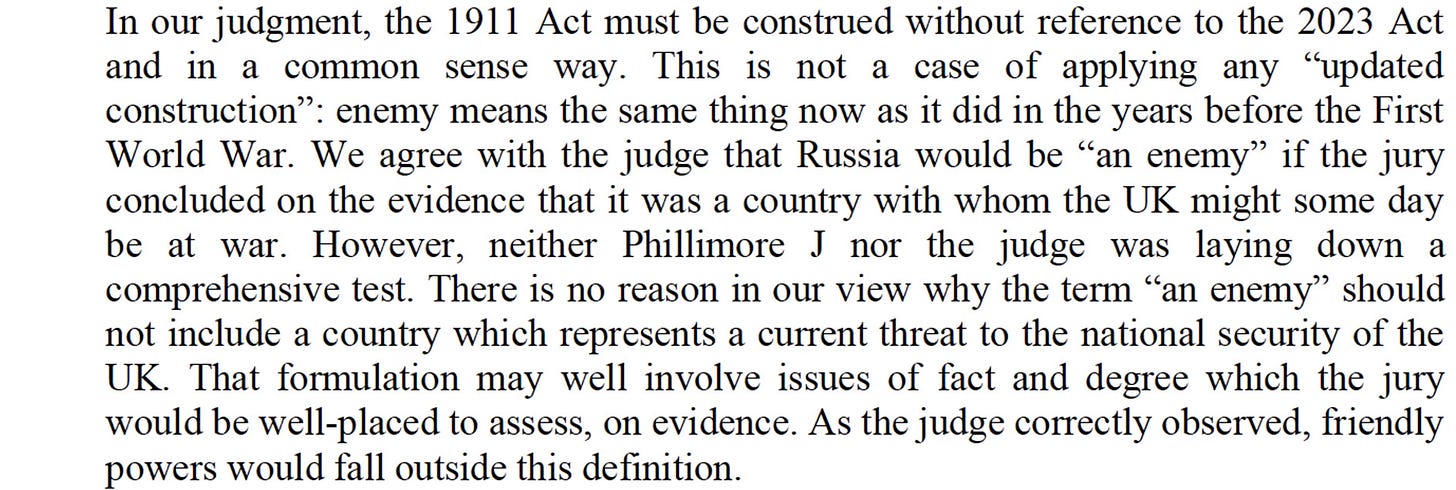

I believe I was one of the first to write, on 9 October, that I was not convinced by the way in which the Crown Prosecution Service had read the Roussev judgment. Here is its concluding paragraph, with references explained in a footnote1:

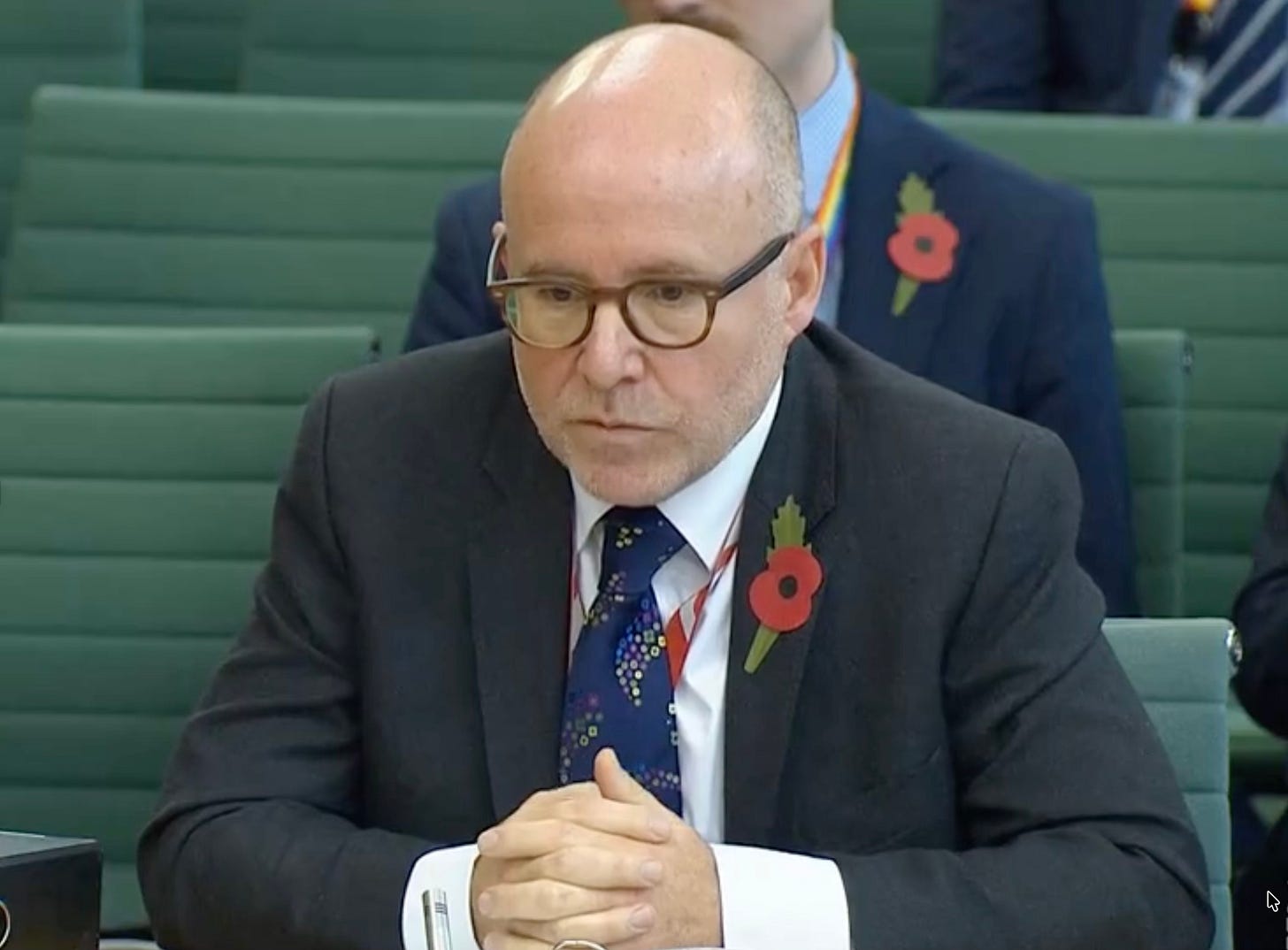

But here is how the case was summarised last week by the attorney general, Lord Hermer KC, in oral evidence to parliament’s joint committee on the national security strategy:

It is important to remind ourselves that the test that needs to be met under the 1911 act is “enemy”. The jury needs to be convinced on the criminal standard, beyond reasonable doubt, in this case that China was an enemy.

The Court of Appeal in the Roussev case… said that you can satisfy that test as a matter of principle if you can show that a country is a threat to national security, but — and this is quite an important “but” — it is a matter of fact and degree.

It does not mean that you can ignore the test of “enemy”: the jury still needs to be satisfied that, as a matter of fact and degree, the threat was such that China was an enemy.

The difficulty in this case was, and would remain if we were still governed by this statute, that it was not simply the case that the government were neutral on the question as to whether or not the threats meant that China amounted to an enemy. The government’s position was that it was not.

On their Double Jeopardy podcast this week, Ken Macdonald KC and Tim Owen KC took issue with Hermer, a former colleague of theirs at Matrix Chambers.

Macdonald thought the attorney general had interpreted the Roussev judgment in a “very odd way”. Referring to Hermer, the former director of public prosecutions remarked:

He said, in essence, it would have been all very well for the prosecution to call evidence to show that China represented a threat to UK national security, but there was a further requirement — and he inserts the word but into Dame Victoria Sharp’s judgment. The word but is not contained within her judgment.

She says: “there is no reason in our view why the term ‘an enemy’ should not include a country which represents a current threat to the national security of the UK.”

She doesn’t then say but. She simply goes straight on to say: “that formulation may well involve issues of fact and degree which the jury would be well placed to assess, on evidence.”

Now, Richard [Hermer] seems to have been saying that that meant that once you’d shown that China was a threat to UK national security, you then had to go on to show that China was an enemy. That was a very strange piece of evidence [to the committee].

Now, Richard — I know and respect Richard and I’m very fond of him — he’s not a criminal law expert. No doubt he did some criminal trials earlier in his career. But if he thinks that a sensible British jury — let’s take an Old Bailey jury, as an example — would have had any difficulty at all in concluding on Matt Collins’s statements that China represented a threat to UK national security, then in my view, he, the attorney general, is very much mistaken.

Owen, a highly experienced criminal lawyer, agreed. Hermer, he observed, had said the jury still had to be satisfied that, as a matter of fact and degree, China was an enemy.

“That’s a reading,” said Owen, “which suggests that this is some separate element — beyond the evidence that shows that China is a risk to the national security of the UK”.

In other words, added Macdonald, Hermer was saying “that evidence that China is a threat to the national security of the UK is simply a step to a further conclusion that it’s an enemy. Whereas what Dame Victoria Sharp is saying is that it is a term which is inclusive in the term enemy and is therefore clearly sufficient on its own.”

Owen and Macdonald were at pains to stress that the defendants denied the charges and had been acquitted on the instructions of a judge.

How did we get to this state of confusion? And who’s to blame? That’s what I seek to explain in my latest column for the Law Society Gazette.

The Roussev judgment was delivered by Dame Victoria Sharp, sitting with Mr Justice Jay and Mr Justice Chamberlain.

They referred to the Official Secrets Act 1911 and the National Security Act 2023.

“The judge” is Mr Justice Hilliard, who presided over the trial of six Bulgarians accused of spying for Russia.

Phillimore J — Mr Justice Phillimore — ruled in the 1913 case of Parrott.

When the Official Secrets Act was passed in 1911 presumably Germany was the threat in mind but obviously war did not begin until 1914 but was Germany not a security threat before war?

Fascinating piece (and so, too, the accompanying article in the Law Society Gazette). There are a number of lawyers now willing to suggest that the prosecution decision-making team of Tom Little KC and Stephen Parkinson, DPP, made a curious decision (putting it at its politest). Joshua is very persuasive, above, in adding Lord Hermer, AG, into the mix for Hermer's apparently flawed defence of the Little and Parkinson's decision.

But I have yet to see any lawyers take the Prime Minister (KC and former DPP) to task for his nonsensical attempt to politicise the matter by taking to the despatch box to blame the Conservative party for the collapse of the trial. There is, however, a non-lawyer's take on the matter (see link below) which looks like it might well hold water.

https://simoncarne.substack.com/p/chinese-whispers-collapsed-spy-case